Happy Saturday!

Here’s what I have for you today:

Housekeeping

What I’m listening to

What I’m reading

Quotations

Housekeeping:

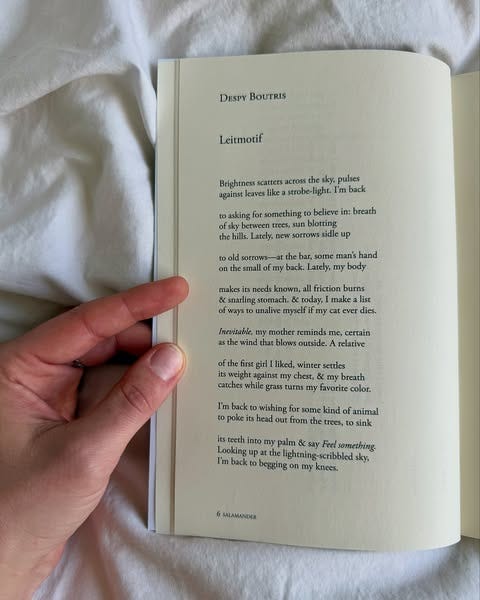

I have a poem out in Salamander. You can read it here:

I also found a Juicy tracksuit on super-sale and am now living out my middle-school fantasies.

What I’m listening to:

This fun cover.

What I’m reading:

What Is Lost When Acid Whey is Removed from Yogurt to Make Greek Yogurt?

How a Devastating Accident Changed Frida Kahlo’s Life and Inspired Her Art

Quotations:

Isn’t the point of writing to exorcize something out of your system? To finally be free of it?? Otherwise you’re held hostage by the muse and your own expectations.

I have been a writer my entire life; I would write and have written for no money, for nobody but myself, and I have grown up my entire adult life as a paid writer for one publication or another, being edited by great editors and terrible ones. I would be a writer without any bylines but my journals in my closet; I will be a writer after everyone forgets my name and any books I’ve written become doorstops in someone’s attic.

I now find myself estranged from the person I was accustomed to being. My body and senses weaken, become unreliable in unforeseen ways, fall subject to illness, and require more attention simply to continue a reasonable level of function. My world is marked by loss and uncertainty.

To become old is to become “other” to oneself, “other” to one’s friends and family, to one’s world. Losses have broken up familiar boundaries, violated definitions, revealed unsuspected landscapes, opened ways of thinking and feeling previously unimagined.

I am grimly aware of the abuses of writing about the Holocaust–of course there’s the phenomenon of writing about the Holocaust that, intentionally or not, reproduces a dominant narrative that centers Jews as eternal victims and then uses that narrative to justify Israeli policy and Jewish supremacy as a form of self-defense.

I think it’s also important, especially with Auschwitz beach reads in the romance genre, to think about why people are so attracted to books about the Holocaust, the sort of fascination people have with the death camps that borders on the scopophilic.

I think unfortunately I’m a very serious person broken by spending too much time in academia but I hope I also have been irreversably twisted by reading so many comics.

Maybe I’m actually just obsessed with researching and archives, I have a classical gay obsession, I’m a normal gay hoarder. Everyone is forced to relate to their families in some way—I think for me to be totally candid I either would have had to divest from them or interrogate them. To make your family an object of study is a strategy of distancing, that also brings you much closer to them.

83 years after my great-grandmother’s relatives died in Auschwitz, what is my relationship to the status of victim, or survivor, or to the circumstances that created Auschwitz, much less to everything that happened after? I’m not a third or fourth generation survivor, I don’t need my neighbors to hide me in their attic, I don’t need to be reminded about the gas chambers every morning on my drive to work. But I wanted to understand how both the actual events and the abuse of the memory of those events shaped me. I talk about this in Heavyweight—I was exposed to Holocaust education throughout my K-12 experience, and in college—and yet I didn’t learn about European colonial genocides, like the genocide of the Herero and Nama people in what is now Namibia, until I was in a doctoral program. And that was incidental, I had to stumble on it.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this distinction, between the project of building alternative Jewish life and the project of being in solidarity with Palestinian liberation and an end to genocide. The genocide happening now isn’t about what did or could happen to the Jews, and I don’t think anti-Zionist art (especially by some random American Jew) is going to be what finally turns the tide. It’s going to be Palestinian-led organizing and resistance, of course. But the art, I guess, will make whatever small difference it makes, whether it’s material fundraising for mutual aid or providing some sort of balm or outlet to help us keep fighting and not burn out.

I find the appeal of fascism to be understandable– it’s about the display of overwhelming power and force, and when you’re a subject of that power, you feel protected, you’re swept up. The problem with fascism is that its an empty container– there’s no actual care or belief outside the violent exercise of power. Which both means that fascism can’t protect you and in fact that you will be victimized by it even if you’re a participant.

I think divorce literature is not actually for women, and certainly not at all for divorced women. Look at who is doing the writing. By and large, it’s an army of unrelatable, privileged white ladies who make a livable wage as writers. The premise of their books is how appalled they are that they could be so let down by a relationship. Their divorce books become a private echo chamber where they can take back the narrative. In their story, these women’s only fault is that they believed in the power of love and family a little too much. And the end of these books is where they use their own pen to re-christen themselves as powerful, brave and honest beacons of feminism. And their resulting story be heard and honored because they had a hard time.

Let me tell you something: Getting divorced in and of itself does not make you a hero, a good person, or even interesting. How I wish that getting divorced was a laudable act of defiance against the oppression of patriarchy, one that also conveniently happens to do work for the advancement of marginalized groups of people. Alas, popular media reminds us that it’s mostly useful as a rebranding exercise, once that paints this cohort of divorcées as daringly defiant divas whose simple act of breaking their vows shot them into a tier of anointed womanhood where they become the enviable torch-bearers of feminine rage, individuality, and autonomy.

Darling, even if we have scarred the earth,

Listen—the owl again in the branches above us

Giving up his position despite the war. And the foxes

Continue to cut the light, the vanishing light and make

Their running in the grass a type of grass

Growing up into a green grain the eye can eat.

Plath did not believe that her art was in any way separate from her politics, which is why her politics took the lasting public form of her art. And this is why we need to stop buying into any voice inside or outside of us which hints that we should be quiet, because this doesn’t involve us. Because we are “only” poets or “only” literature scholars or “only” fans. No art exists in a vacuum. All art is a vital product of its world. So if you make art, or you love it, you have to stand up against a country hellbent on destroying the creative solidarity that builds a better world, a world free of state-sanctioned murder and the violent repression of speech.

Do you think your art, or the art you love, will be spared, under fascism? And even if it is—can you still love it? What is that love worth? How will we face what is left to us? How will we face ourselves?

That’s all for today—

-Despy Boutris

Instagram

Twitter

Website

Dyke Semiotics

Zines

Shirts