Happy Saturday!

Here’s what I have for you today:

Housekeeping

What I’m reading

Quotations

& a disclaimer, again: Things are mostly terrible right now, and the violence is appalling, and there are many people out there who have addressed and do address it better than I ever could, so I’m not getting on a soapbox here—this will just be your weekly round-up featuring what I’ve been reading and thinking through, like usual.

Things to read:

An Israeli operation rescues four hostages and kills scores of Palestinians. Here’s what we know.

UN says Israeli forces and Palestinian armed groups may have committed war crimes in a deadly raid

Housekeeping:

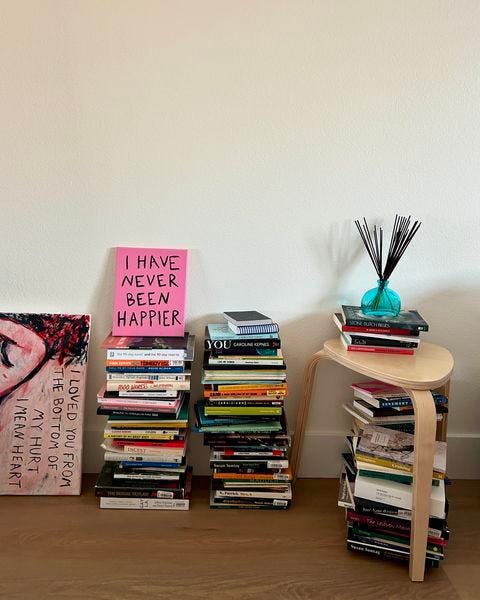

I am slowly moving into my new apartment. Look how sweet.

She did this for me:

Also: this is so good.

What I’m lusting after:

This color of nail polish (I don’t wear nail polish but always aspire to, in theory)

What I’m reading:

Quotations:

I was relieved to be diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder because I’d actually known the diagnosis to exist for over a decade before it was given to me. There’s a quote from my second book, The Collected Schizophrenias, that I often refer to. It says something like, “Some people don't like diagnoses, disagreeably calling them boxes and labels, but I like to know that I'm not pioneering an inexplicable experience.” This is very much how I experience it. I like to know that generations of people have been through similar experiences to mine, even though they're frightening and have caused me much suffering.

The most important part of a writer’s education is reading. You have to love reading; you have to be crazy about books. This may seem obvious, but I have sometimes asked nascent writers what they’re reading now, and they have replied, “Oh, I don’t have time to read.” It would be like a musician saying they don’t listen to others’ music, or an artist not looking at other art.

All my characters are still inside me; some quieter than others, but they all still live on.

Ultimately it doesn't matter that I select the absolute optimal ideal place into which to put my energy, because frankly I am not important. I just need to show up and do whatever it is that I can to fight injustice, build community, and resist settler-colonial, capitalist empires. There will always be plenty of work left for the next person to pick up.

It was absurd main character energy to expect myself to do everything or to be able to "save" people. And yet that was exactly the kind of moral burden I was putting on myself for a very long time. And it led to periods of intense overcommitment followed by burnout, spreading myself to thin, and most crucially, failing to attach any of my furious efforts to the work of an enduring, tightly knit COMMUNITY.

There is something kind of insidious, no, about the increased expectation that an author is to turn themselves inside out and slather their personal histories across the page. Identity used to mean a particularized set of experiences unique to one person. My identity. My self. Who I am. But now, identity means one’s belonging to an affinity group based on some shared trait. Identity used to mean something loose and changeful. We grow, we change, we find out things about ourselves. And now it means something hard and permanent. Unyielding. Determining. The immutable parts of your life.

For the last half-decade, writers, critics, and readers have been wrestling over what to make of Yanagihara’s affinity and fixation on brutalizing gay men in her fiction. I personally don’t care. If the book is good, it’s good. If it’s bad, it’s bad. I don’t really think she owes her readers anything in terms of affinity between her identity and her characters. But I do think she has a tendency, on display in A Little Life more than in To Paradise, of torturing characters for the sake of her own facile arguments about the nature of suffering.

The fact is that, yes, some fiction is biographical. Some fiction is not. But most things in fiction do come out of life one way or another. Is this interesting? Is it striking? Turning something that happened to you into art? Is that more interesting than the art itself? Something happening to someone is the most boring and common thing in the world. Things happen to all of us. We all have stories we tell about what was done to us and by whom. Stories we tell to ourselves. And to few, select others. All of life is made of such stories, no?

I don’t know what it is but since I became friends with other writers and moved to New York, they all want to eat raw seafood. Like, a lot. But the thing is, I can’t really eat seafood. Not because of dietary reasons, but because of the fact that I was once raped in a house that smelled very strongly of shrimp. And not just that, but that was a summer in which everyone in my family was eating shrimp. Every night for dinner was shrimp. Everywhere I went was the smell of shrimp. And this guy, my aunt’s boyfriend, was molesting me. And no one would do anything. And it was just shrimp, shrimp, shrimp. And now I can’t eat shrimp because it reminds me too much of being raped and of that summer. But here I am in trendy hand roll places or out at sushi restaurants with friends, people I love, who love me, and here in front of me is shrimp or other raw fish. Which I can’t eat, except I do eat, because I don’t want to have to explain about being raped. And just like that, I am living two moments simultaneously. The one in which I am in New York, with my friends, and the one which I am in Alabama, in the dead of night, running home on bare feet over broken glass and pine needles trying to get to safety. Except the shrimp. It’s the one thing I can’t make myself eat, no matter what. The other fish, I can gulp down and try not to smell. I can get through it. But shrimp is a real no-go zone for me. I try to smile and say, “Oh you can have mine. Please.” But then there’s always the do you not like shrimp? And then it's like, do you ruin the whole night with your trauma or do you just smile through it and make something up. And then, of course, the whole next day, I am sick to my stomach and can’t get out of bed because, obviously, I can still smell the fish and I am still thinking about that summer, about the pine needles and the wet ground under my feet, about the glass I had to pick out of my soles in the bathroom when I had finally gotten home, about the way he’d shown me his gun before he raped me, so I’d be afraid, too afraid to run. And I’m in bed and can’t get out of bed and spend my days, guess what, in a fucking fugue. All because I ate the raw fish and smiled through it. Because I didn’t feel I could say anything about the trauma. And on.

I am often moved by literature. Moments of genuine human feeling. I think sometimes, authors try to capture trauma’s evacuating quality by leaning into plainness and aridity, and they forget that people do have feelings. Even traumatized people. Even if they can’t access them, they do have feelings.

Trauma does have a host of narrative and expository tools at its disposal. It does provide an out for a floundering writer. And it does, or, can suggest itself, as though it were an epiphany or a revelation. There have been moments in my own writing life where I’ve been stuck on a character, and felt an unlocking sensation at the thought of it, Oh, they must be traumatized. That’s why they’re so withholding. But usually, this can be fixed by simply giving the character something to do. Some means of surprising themselves or others in a scene. And then building on that. Alternate routes exist.

It’s kind of funny to me because I feel like what first drew writers to what she calls the trauma plot was the freedom it offered from other forms of handy explanation and psychologizing in fiction. Trauma, with its obliterative and annihilating force, could derange and deform the comforting narratives of life. It opened a way into fragmentary, associative storytelling. Trauma made fiction look more like life with its randomized assortments of thoughts and images. But now, we have the accusation that trauma is somehow an ordering mechanism. That it marshals narrative into a couple of distinct forms. The recursive and the static present. Which, very funny and ironic, to me personally. But here we are.

The trauma plot strikes me as a name we might give to fiction in which there is simply no there there, you know? Like, fiction that gropes toward or gestures at some shadowy region of the human experience because it has nothing really interesting to say about being alive. And, yeah, one can get by with some style and giving a character a dead ethnic parent or homophobia to deal with. You can. That is true. The bar seems tantalizingly low at the moment.

We had both decided we’d like to get married, start a family, own a house with a big yard where we could build a garden and watch our dogs chase each other around. Blame it on my sun in Cancer in the 15th degree, but I’ve always wanted to have kids and find a life partner to grow old with. Not even the political pressures of the queer community could sway me from the unshakable inner knowing that I would make a great dad and hubby if given the chance. I knew straight away that AJ was the type of person that I could spend the rest of my life with if I was lucky. Getting married to each other is just the cherry on top.