Whenever the subject of exercise comes up—and it does often, because I am mentally ill and all the wise, health-conscious people in my life know the objective benefits of exercise as a factor in improving mental health, among its million other benefits—I say the same thing: I hate exercise. I say, quite plainly: I prefer to think about the body as little as possible.1

I have fantasized more than once about being a floating brain with nothing attached to it—no body, nothing to see or perceive, the body and mind wholly separate.

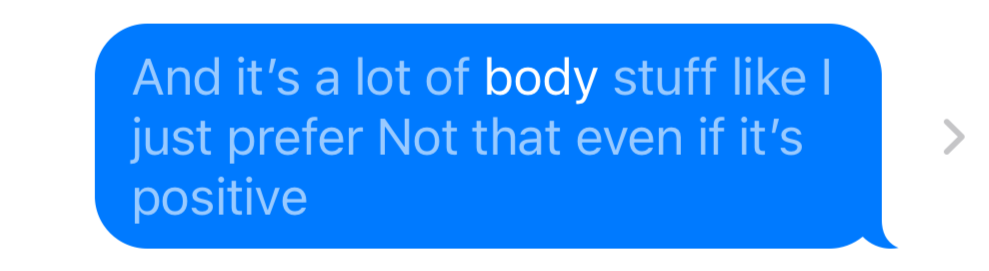

I follow fitness enthusiasts, influencers, chefs, and bakers, who speak clearly about their bodies and everything they’ve learned about them: they say, I love this recipe because it fuels My Body, or they say, I’ve learned what My Body needs, or they say, My Body was telling me something was wrong.

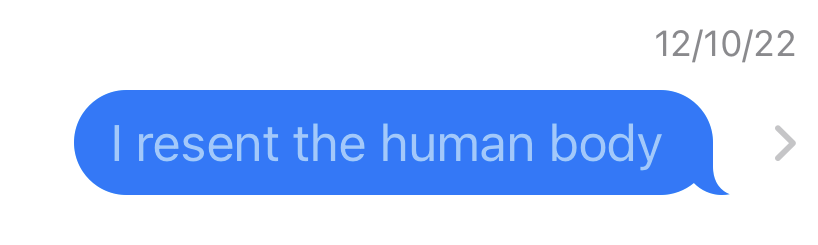

For me, “body” is not a my but a the. I want to keep it at a distance, distinct from the self, and to pretend that it’s not enmeshed with the head and with everything else.

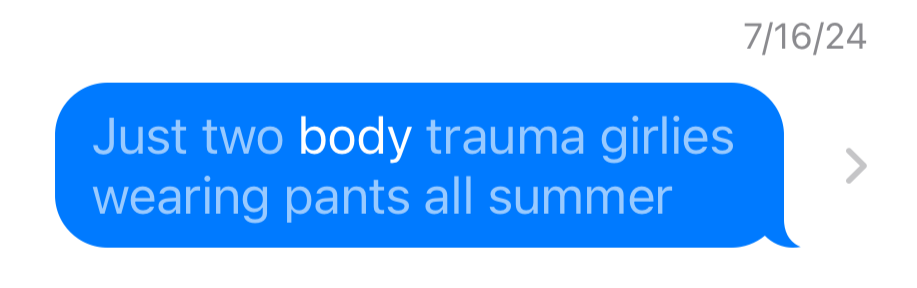

I have never particularly liked The Body. As a child, I always had nosebleed-stained shirts, or was always tripping over my own pigeon toes. And then, later, like any teenage girl, I was subjected to interventions after missed meals, quiet obsessions.

I think that one way I escaped my adolescent disordered habits was to stop thinking about The Body, period.

Back then, I was too aware of The Body, thought of it over everything, all the time. Back then, it was progress—to, finally, not think about it anymore.

But, now, at the ripe old age of 28, I have learned that I have elevated cholesterol levels, despite not actually ingesting any in ten years (vegan), because the body makes its own and also apparently exercise (disgusting) plays a role, too.2

And so, doctor-pleaser and recovering-perfectionist that I am (even about my yearly labs), I have decided to slowly begin to uhhhh exercise.

It is not fun at all. Some people love exercise and I love that for them, but I am weaker than I look and it feels terrible and I would always rather be sitting than moving. Better yet, I’d rather be lying supine.

Movement feels even worse here. Back in my hometown, I could walk to the bookstore or find a trail a few blocks away but, in LA, every hike is a drive away, and the last thing I want to do after a workweek is drive some more. So I’ve started to walk on an incline on my roommate’s treadmill a few times a week. I’ve started to pick up her docile 13-pound cat—dead weight in my arms, happy to be cradled, his head tilted back—and do ten squats on days when he follows me into the kitchen and I remember.

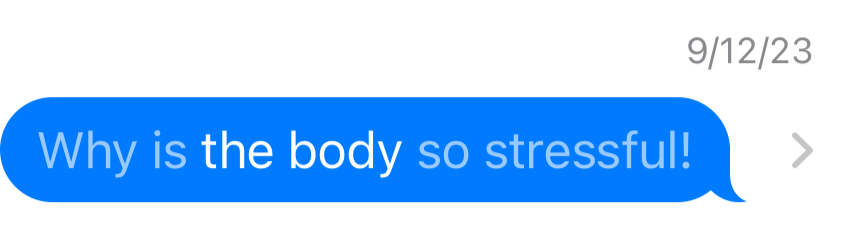

I am not weight training and not gaining muscle, as far as I can tell—just getting into the habit of movement, despite the forced awareness of The Body that comes with that, its rotations and heaving breaths (ridiculous—The Body’s need to take in oxygen, its refusal to ignore that need).

Yesterday, my physical therapist said, I’m going to press against your right leg but, whatever you do, don’t let it fall. She applied the slightest pressure and it collapsed down onto the other, a failed test. Embarassed, I said, To be fair, I’m left handed. She perked up, tried the left leg next. Just as weak, no better.

She gave me new homework: “supine bridges (single leg)” and “clamshells,” whose name reminds of this scene in But I’m a Cheerleader, somehow. The slow opening, I guess, like an orchid, or a clam. I did three sets this morning, legs shaking and resentful.

My mother, the health guru in my life, says it can take six months for cholesterol to go down after changing one’s habits. So, for five more months, I will continue to throw on a pair of shorts and a sports bra a few times per week and endure the forced awareness of The Body, muscle, of having a form and a shape.

For five more months, then, I will hope to adapt and to stop hating the act of movement, the fact of The Body, because—like those health-conscious people in my life (my parents, my brother, my fit friends) claim, movement really does help one’s mood, apparently.

Being on the maximum dose of Zoloft for a few years did not help my mood and what would, realistically, help most is not being quite so far below the poverty line but—pending efforts toward becoming more employable—I’m hoping exercise helps my mental anguish over uhhhh *gestures vaguely* everything that’s going on in the world, all the time.

I’m not looking for body neutrality so much as to lessen the fissure between the mind and The Body—the cut separating my mind from the soft flesh of me—to stop fantasizing as tweenage boys do about sex about the ecstasy that I imagine would come with being a floating brain, bodiless, utterly unperceived. I’m old enough that I’d like to fantasize about bigger, better things: about having my very own garden, maybe, or about someday finding someone I love enough to pull a Miller and Shellabarger and dig a tunnel between our graves, bodies disintegrating together. And, someday, I’d like to fantasize about those parallel graves, hands held in the hole between them, for the love alone—the desire for remaining united even in death, and not for the twisted romanticism of comingled goo and sinew.

I don’t have to like movement, though I hope that forcing myself to move improves my cholesterol and that the endorphins restore my verve for life, at least for the few hours that follow each 3-mile walk.

I don’t have to like The Body. I don’t like it and I don’t want one. But I have one and my mind’s inside it and it’s mine.

Despy Boutris

Instagram

Twitter

Website

Zines

Shirts

I’m fine, by the way. I’m totally fine and normal. If you think this sounds weird, I’m fine, I promise.

So do genetics (gross) so, if exercise doesn’t successfully move my levels into the “normal,” “acceptable” range, I’m beyond hope, I guess?