Happy Tuesday!

Here’s what I have for you today:

Housekeeping

What I’m reading

Quotations

Tweets

Housekeeping:

I compiled your favorite newsletter posts of 2022 (along with my personal favorite books & skincare this year, because why not). In case you missed the email, you can view the post here:

It’s prize nomination season!

I nominated a number of poems for this year’s Pushcart Prizes—and some of my own work was nominated by other journal editors. I’m so grateful.

What I’m reading:

A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America

Why the Vibe Shift Might Finally Leave the Kardashians Behind

To read:

Quotations:

More thrilling than holding her hand in public, appalling the religious, or feeling superior to heterosexuals was being able to say the words my girlfriend.

The pleasure this elicited came from someplace old, older than the adolescent urge to shock or infuriate. Saying my girlfriend produced the satisfaction of a child declaring their age, right down to the month, for the benefit of an inquiring adult (“Seven and three-quarters!”). I was not one of those little girls who wanted to get married; the phantom I was supposed to have been would likely have spoken of her future husband the way I say my girlfriend today, which remains: bashful, arch, incredulous, smug.

I started, almost daily, to have unprompted moments of tectonic emotional intensity, where I would literally leap out of a chair and blurt out “what if I didn’t have to keep feeling pain about all the bad things that have ever happened to me?” and mean it, deep down to my neurons.

Dissociation is adaptive in a way that can’t really be rivalled. You have the capacity to not be yourself to the extent that it will ensure your survival. I can’t think of a greater power, heavy though its cost may prove to be, especially over time.

What do we mean when we (trans women, I suppose) say our being (trans) is not a mental illness and isn’t a medical condition? It’s not so much a scientific counter statement as an indictment of the eugenic uses of “mental illness” as a form of social stigma and political justification for captivity and depravation. It’s a century-long assertion in the making, uttered by the first femmes who disagreed with how the sexologists Richard von Krafft-Ebing, or Magnus Hirschfeld, ignored their autobiographical testimonies in favor of pathologizing them, and uttered still now.

The use of dysphoria to describe trans people is, more importantly, insubstantial. In the first place it reflects an incredibly recent shift in nomenclature. The OED can catch us up quickly: the term dysphoria didn’t emerge in English until the mid-nineteenth century. It’s first usage, in 1842, was to describe an emotional state of “dissatisfaction, restlessness, and suffering.” Anthropologists and sociologists developed this emotional description by studying “primitive societies” and “deviants,” with one 1933 study describing “a condition of dysphoria” as “when people feel shamed” for socially stigmatized behavior. In the mid twentieth century it continued to describe states of feelings like guilt, shame, and general emotional distress caused by one’s social environment.

This is why gender dysphoria is not actually a trans term. It merely specifies the arena in which dysphoria is concentrated: I experience emotional distress like fear, guilt, or shame, not because I am trans, but because my gender is treated as abnormal, illegible, dangerous, or undesired by the social world in which I live. This might manifest phenomenologically in my flesh, for instance, when I think my shoulders too broad, or my breasts too small, but it is because I fear how I will be treated when others assign and surveil my gendered body. I fear the penalties of my culture for my disobeyant form.

There is, in other words, no idiopathic medical issue, which is not surprising to us because cisgender is a fictional story our culture tells itself. Dysphoria describes a social situation of transphobia where transphobia—as in, animus towards and danger manifested towards trans people for their very existence—is the result of a social world where cisgender is granted immense power as the “normal,” default category of human experience.

Every time you melodramatically invoke your concern, or interest in studies and numbers, I see your admission that you are in want of a justification for your aggression, for your eugenics, and for your authoritarianism.

As trans people, we are symbol and proof of the world’s unraveling, which sounds pretty dramatic until you’ve been on this side of things. n our realness, trans people expose systemic artifice so foundational that departing from it in thought or deed can literally drive you crazy. Confronting that is terrifying, especially if you’re cis, since in that case you actually have something to lose if the whole thing were to ever come tumbling down. This means, incidentally, that cis fascination with us is also about power. But when is gender not about that, too?

If we’re defining the chaser as someone who calls their obsession with your gender love, then my first chasers were probably my parents.

I don’t think the closet metaphor goes far enough when understood in this way. For me, closeting was not like wearing a mask or a costume, allowing for at least some part of “the real me” into the daylight. It was like being dead. Gender organizes how we share information about ourselves—that is, it’s how we communicate. Our genders inform and shape how we are polite and rude, gentle and violent; how we convey want, need, desire, and interest. Like age, race, class—a whole mess of things—gender (like community) is something you do. Even agender people must interact with people with genders, in cultures and milieus organized around normative gender, and are beholden, on some level, to gendered interaction, particularly in how others understand them. Without your gender (or lack thereof), as you understand it, you are nothing. Maybe, like me, you’re spiritually dead. Maybe, like trans people without the luck and safety I’ve had, you’re literally dead.

In any case, with exceptions like the luminous Moonlight, I tend to avoid Oscar-bait and critically acclaimed flicks about gay people, and flat-out ignore them if they’re about trans people. The payoff aint worth the risk of having my feelings hurt, and I despise seeing straights make money for playing queer at no professional cost.1

The first feeld poem I wrote that made it into feeld is “the mothe bloomes inn the yuca” and I conceived it as being the opening poem, because I had thought of the collection, initially, as more treatise-like or phenomenological, where an “I” reaches out and touches things (insides are becoming outsides, outsides are becoming insides). A strain of that is still there thematically; however, this ended up not being what I felt was primary to the collection. Instead, it felt like the trajectory of this “I” in the world is what needed to be the focal point. In light of this I felt like it was important to begin with the poem that begins it, which is this poem where the “I” is in the feeding mart, wanting the dress, wanting the skirt, and sort of playing around with the trans narrative and the expectations that a reader might bring to that narrative.

History […] is not the “true story.” Rather, it is a story as best we can tell it, given the evidence, our own assumptions and values, and the perspective we take from our own place in a particular society at a specific point in time.

-Leila J. Rupp

From sodomy trials we have evidence that same-sex activity did take place among both sailors and pirates. […] Were these simply cases of men, lacking access to women, making do with what they had? Did men inclined to such relations perhaps seek out seafaring occupations?

-Leila J. Rupp

Our modern categories of heterosexuality and homosexuality (and even bisexuality) are not complex enough to capture the slippery reality of love and desire.

-Leila J. Rupp

As long as they did not cross the lines of respectability in some way—by appearing “mannish” or utterly rejecting men […]—romantic friends may have had quite a lot of leeway to express their love and desire.

-Leila J. Rupp

We felt to each other at once. […] Something in him drew me that way. […] We were familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood.

-Peter Doyle, on meeting Walt Whitman

Sexual difference can be seen as a form of dissent.

-Leila J. Rupp

When you actually define “feminism” — a political movement toward collective liberation — it’s clear that cosmetic surgery is not feminist. It doesn’t collectively liberate. It’s an individual “solution” to systemic issues — one that, in most cases, reinforces said systemic issues. That said, I don’t think every single action we take in our lives must be an explicitly feminist action! The most harmful thing about the “aesthetic modification is feminist” argument right now (IMO) is the impulse to recast our every individual behavior as “feminist” and therefore absolve ourselves from critique. It waters down the collective understanding of feminism, it minimizes the work and sacrifice that actual feminist practice takes, and (for many) it replaces the urge to do the actual work of feminism because we already feel politically active from getting “work” done on ourselves. I think the people who make this argument are, at their core, unwilling to give up standardized/industrialized beauty as a form of power (because it’s one of the few forms of power we have) and are instead trying to manipulate it into something radical when it’s not. Also, not everything that makes you feel “good” and “empowered” and beautiful is feminist! Lots of beauty behaviors only feel “good” or “empowering” because a shitty system of oppression made sure you felt bad and stripped you of your power first, in order to force participation. Like if we can't stop perpetuating oppressive beauty standards via cosmetic treatments, can we at least stop perpetuating the idea that they're feminist?

Call to action:

It’s the end of the year, which is a great time to take stock of your recent successes & future goals.

You might ask yourself

what publication from 2022 am I most proud of?

what literary journal do I hope to appear in next year?

&, of course, I’d love to read your newly-published work, if you’re open to sharing it:

Tweets:

& before I go, one more question for you:

Be safe out there—

& please consider buying some lightly-used books (US only) to help me pay TWR contributors! I can’t do it without you!

-Despy Boutris

Instagram

Twitter

Website

Shop

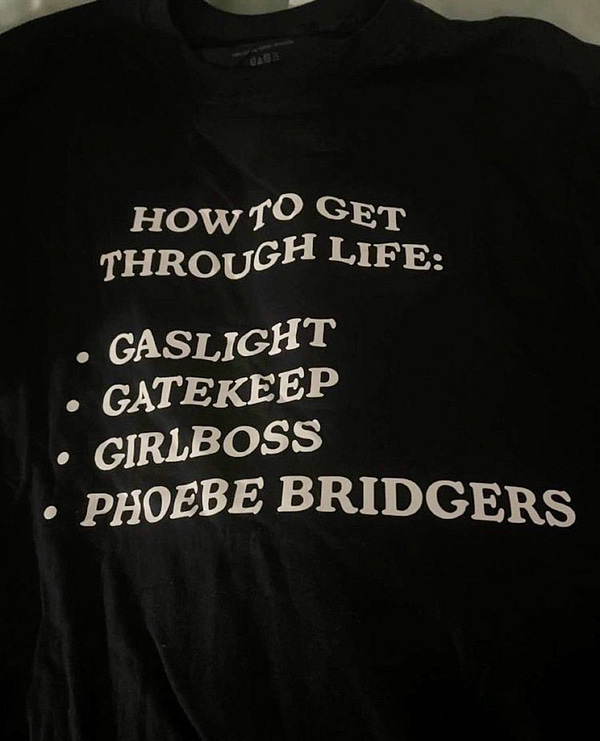

mood.